This project was developed during my time at Roundtable Residency, an online, artist-run residency program, in the summer/fall of 2022. You can also read it on the Roundtable Residency 2022 exhibit website, and check out work done by the other residents. <3

Is a rock alive? What story would it tell if it was? A Rolling Stone Gathering Moss began by stumbling across a rock in the path. Taking on the rock as a subject, I attempted to document it in an ongoing series of transformations from photogrammetry to augmented reality to drawing to 3D simulations and onwards… only to ultimately fail in finding a conclusion. A Rolling Stone Gathering Moss is a breadcrumb trail of artifacts from the appreciation of a stone.

This project started in the middle of the summer. I had just moved to a new apartment that’s by the Hamilton mountain cliffside, and I was going on these short daily walks through the woods there. Walking in the woods both reminds me of my body and allows me to think through the things in my head. I started noticing that there were these textural, mossy rocks in the middle of the pathways– sitting just off to the side, or emerging from the ground. I probably tripped over the first one.

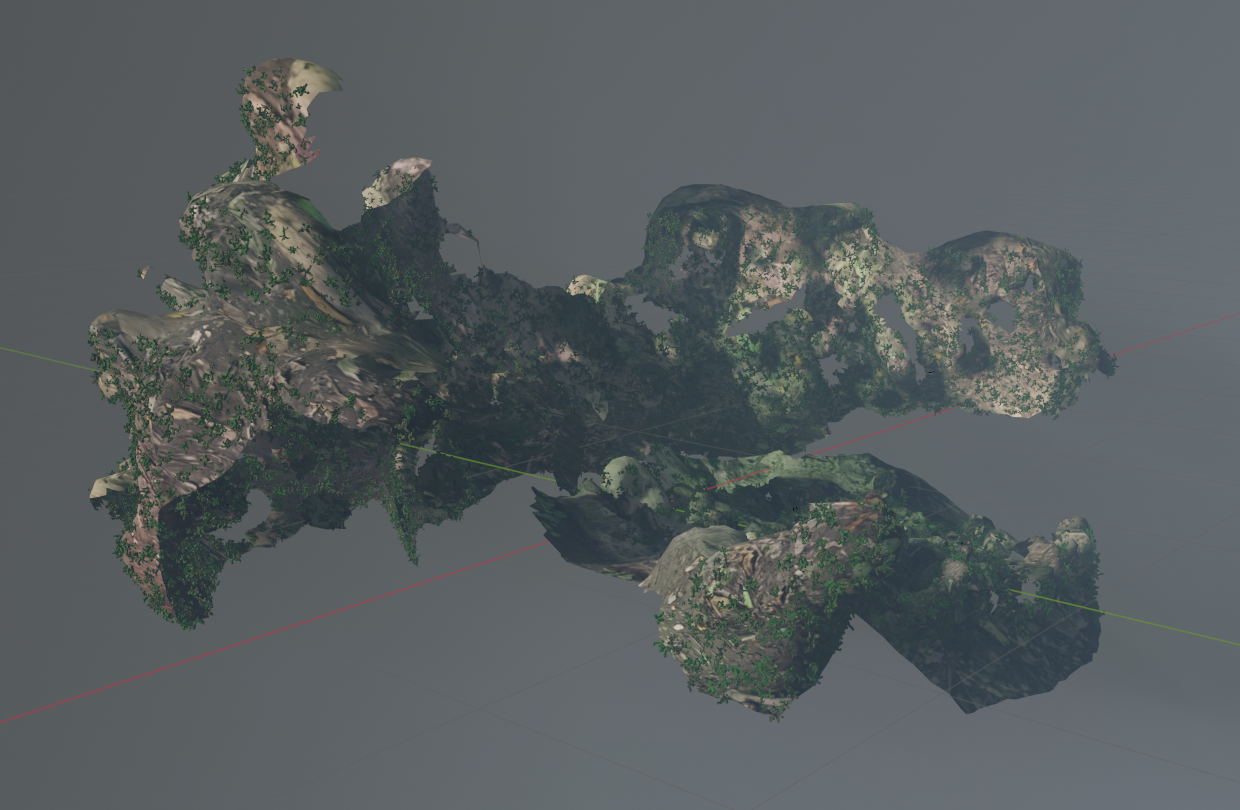

At that time I had found a free-to-use photogrammetry program that I wanted to try, so I tested it out using photos of this rock. Photogrammetry uses a set of photos of the object taken at different angles and compares the photos’ pixels to figure out what’s similar and different, generating a 3D model with depth from these guesses. It’s not dissimilar from David Hockney’s photo collages– an even better, Osang Gwon’s physical photo collage sculptures.

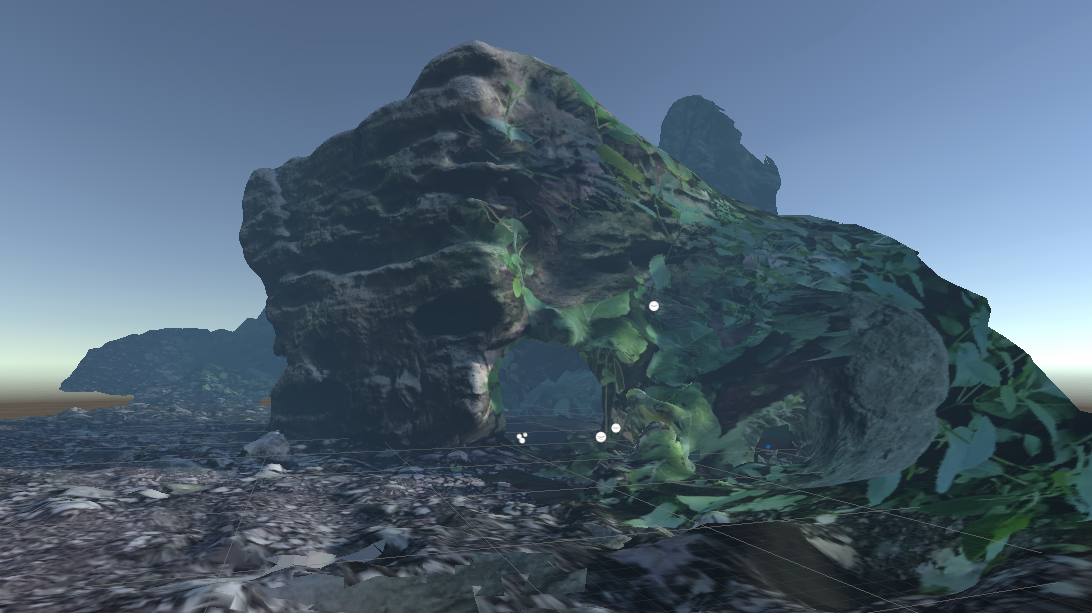

To my chagrin, the result looked nothing like the actual rock. The model’s mesh (3D form) was glitchy, a kind of rolling blobby mess with bits floating mid-air– and the results became more and more distorted as I tried different settings in the program. Yet when it applied the generated textures to the mesh, they contained parts of the original photos, so you could see some of the accurate colours and textures coming through.

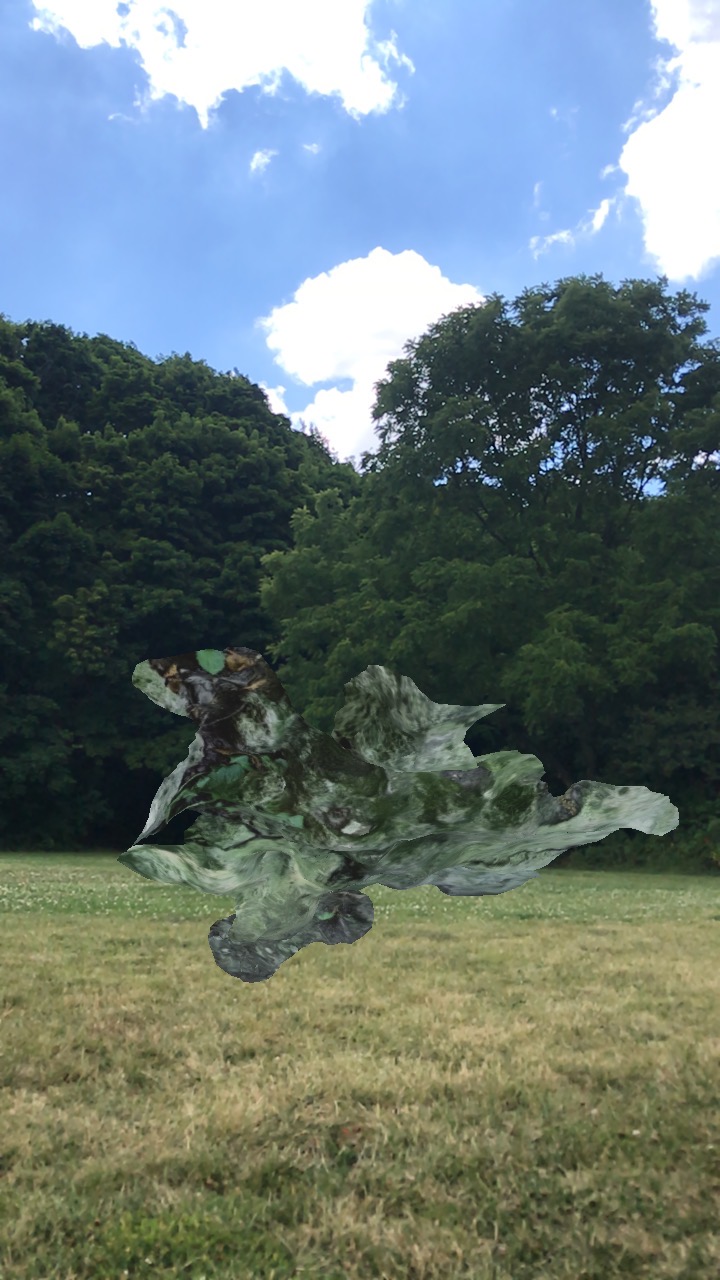

I had also wanted to try making an augmented reality app using SparkAR (Facebook’s program for face filters used on Instagram) so I exported the generated rock’s meshes to Blender and then SparkAR. I uploaded a demo to my phone which I took with me on another walk so I could view my poor 3D model in relationship to the actual rock IRL. There’s something about augmented reality that reminds me of magical realism: you’re seeing what’s actually there and familiar to you, yet you can also see this additional layer over reality, through your phone. I remember in Zelda there was a tool called the ‘lens of truth’ that would reveal invisible objects and see through illusions. AR is reminiscent of this, in that the digital world is this kind of invisible layer that still has some kind of presence. The 3D physical space gets compressed into 2D through your camera, and then the program tries to understand it as 3D space and insert a form into it.

So that was cool. But I wasn’t quite sure what to do next. I took some screenshots of the AR application and thought about using this as a kind of image composing process that I could use to for paintings or drawings.

I had the 3D model in Blender, too, where I could fly through space and orbit around it. The model on my computer screen felt even bigger than the rock, like a kind of landscape I could explore, so I tried adding lighting and fog to create a sense of depth, and even moss growing on its surface.

I wanted to see if I could get a better, ‘truer’ documentation of a rock, however, so I tried the photogrammetry with two others. The third stone, an oblong cuboid, was the closest I came to an accurate scan.

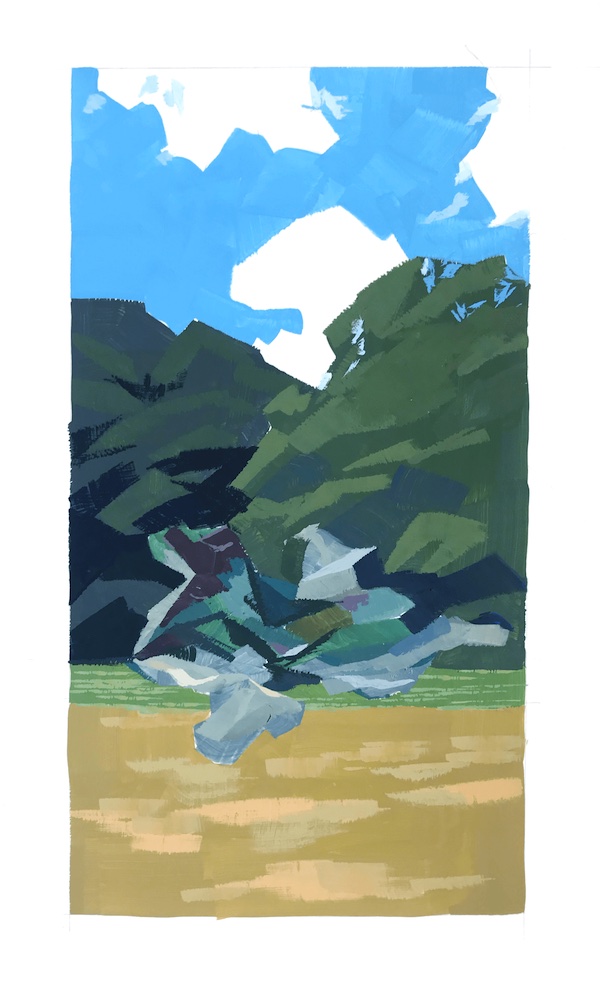

I also found all this time and energy of mine spent looking at and working with this rock, kind of funny. It was just a rock, afterall, one of those objects classified in my head as ‘normal’, ‘everyday’, and therefore fairly unremarkable. Why was it that this was living in my consciousness for so long? When this started, I took the rock as a specimen, something to document and then test these technological processes on. But at some point, perhaps during one of the many morning walks where I would meet this stone again, it became more than a rock. It took on a kind of life and presence, personhood. First camera and computer tried to capture the essence of the rock and failed, then I tried to capture it with my eye and hand. I turned back to traditional materials and drew portraits of the rocks.

I remember talking about this series with an acquaintance who was a geologist, about how a forest feels alive whereas a rock doesn’t. But standing on the path with this stone, it didn’t feel dead to me. I wondered about its story, how had it gotten there? Had it been sheared off the cliff at some point, rolling down and settling on the ridge? How had its body been carved by the elements, and for how long? The timescale of a rock is completely different from our own human one– trying to understand it is an exercise in imagination and empathy.

And my 3D rock was so obviously not the one I was communing with in reality. It didn’t have the weight and density of real rock; it was a hollow shell, an illusion.

At this point I started exploring the materiality of simulated 3D surfaces. It was vertices in space with a gossamer-thin pixelated image stretched across its faces. I thought about revealing this aspect, so I tried simulations where the rock was cloth being pushed by a wind. The rock model looks solid until the simulation starts, then gravity immediately begins pulling it down while the wind pushes the collapsed form off the ground plane. Next I tried directing the wind underneath it, to inflate the mesh like a balloon. I like how the rock suddenly turns into this weird ghostly blob that hovers in the air, like an animated spirit.

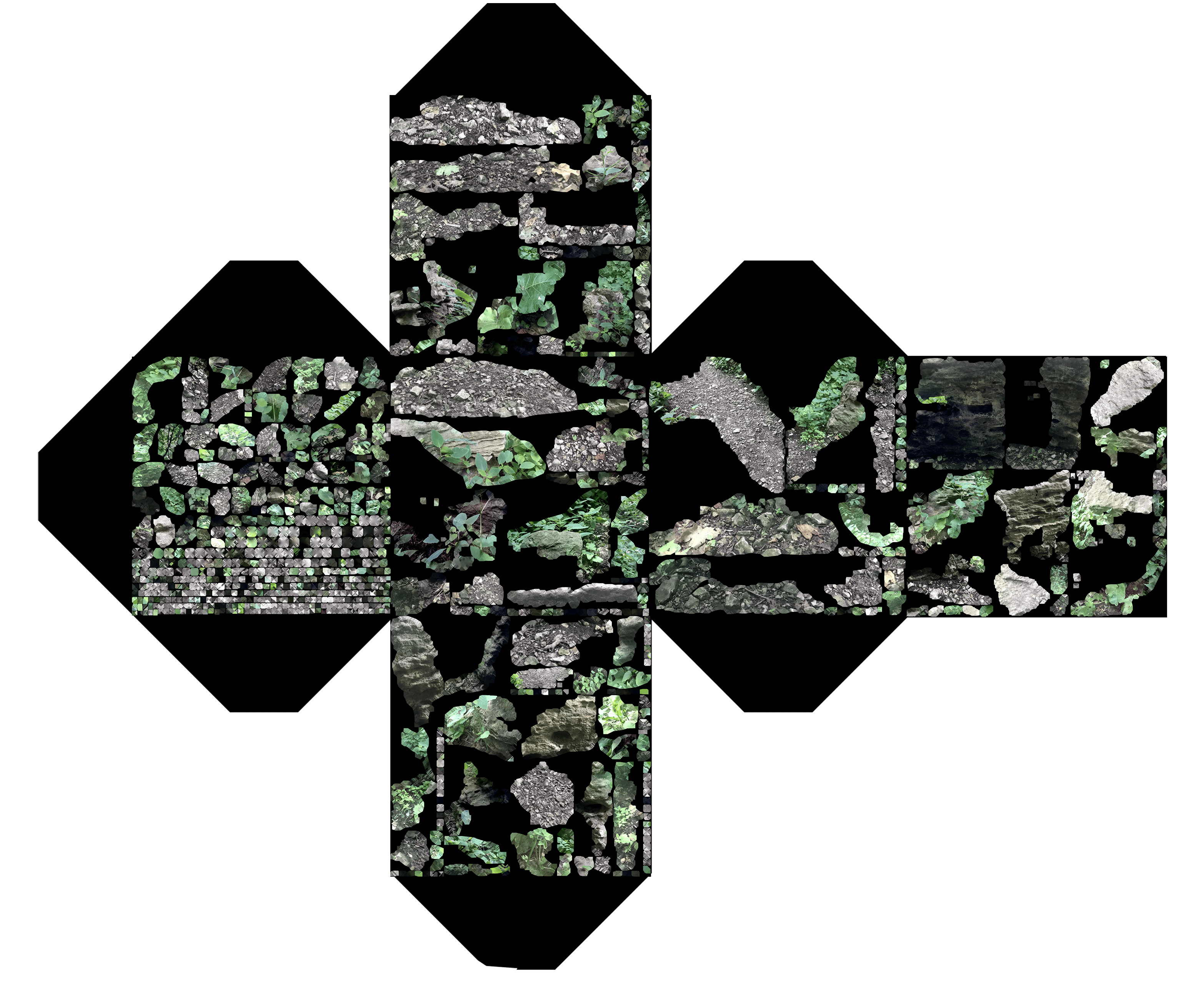

The texture maps generated by the photogrammetry were also interesting in their own right as images. You can see islands of photographic greenery and the actual rock textures, as well as dozens of tiny fragments the program couldn’t quite figure out were connected to larger faces. I was interested in creating some kind of physical object that you could interact with and had been exploring simple paper geometric forms, so I laid out some of the images from this series onto them, printed them out and assembled them. I thought the fragile, hollow paper forms were kind of a physical representation of the 3D model’s fragile mesh, too.

Generally speaking, in western culture, a stone is a stone– we don’t necessarily have a formalized designation of remarkable or artistic stones, unlike East Asian cultures (and probably in others, as well). In Japan, suiseki are stones appreciated for their aesthetic values, in China this is called gongshi, in Korea suseok (the rock that features in Parasite is an example).

“It is not a silly thing at all to enjoy a stone in a tray. I see the whole world in a tiny stone. Some objects in this world are huge, and others are small, and they come in all shapes, but they are not that different when you look at their essence.”

- Hideo Marushima

The rock’s faces are beautifully textured and sculpted, the moss lush and spongey. I wondered what it would be like to be one of those tiny organisms slowly travelling across the surface of the rock. The phrase “a rolling stone gathers no moss” had been living in my head for a while as well. It refers to the idea that if a person doesn’t stay in one place they can’t form connections and relationships that would ultimately have value to the larger social web. But so far in this project, each time I ‘rolled’ the rock into a new media or form, from photos to 3D model to AR app to painting, some kind of growth or transformation was taking place. There’s a whole world in a tiny stone, and in the same sense the whole planet is a large stone. A stone rolling through space, host to organisms.

I came back to my scaled-up 3D version and took that into the Unity game engine to create a simple walking simulator, so that I could explore the surface like one of those little organisms. You can literally fall off the edge of this ‘earth’. Again, the 3D form isn’t solid, so you could ‘clip’ through the mesh. And I kind of liked that, because you could never walk into the rock in real life– but here I could open up an entrance into the body of the rock, and walk right into it like a building.

At this point, I was getting to the end of the Roundtable Residency and trying figure out where this was all heading. I had ideas of where I could push it further, but they felt like separate yet interconnected roads– the paper forms, the walking simulation, the AR app. I wasn’t sure where to go next, what the big takeaway or product was.

Perhaps there isn’t one. In Japanese gardens there are sometimes rope-wrapped stones sitting on a pathway. These are tome ishi, a gentle symbol to go no further, to not take that path. Perhaps I could’ve benefitted from some of these in this project.

Artistically, I was reminded through this project of the value of “research through making”. I was able to keep up interest and explore this rock over months through the momentum of moving between mediums and iterating. I kept trying to record this rock and kept failing– classic (wo)man vs nature. Perhaps like suiseki, this trail of images, objects, and interactive experiences are meant to be artifacts of my appreciation for these stones.

I went back to visit the rock recently, after not visiting for a while, and was dismayed to find that somebody had spray painted all over the rock. And while I have photographs, drawings and even everlasting digital files of this rock, ultimately they can’t ever replace the original. Once these things are gone, they’re gone. Even bodies such as stone, as stoic and unchanging as it seems, change over time. But the stone, however its form changes, will most likely outlive the products of this project.

Stay tuned for an update to this project in the (hopefully near) future!