Hello again! I’m here to share some of what I’ve ✨learned and found✨ this past week: walked around Cable Wharf by the water where the Transatlantic cables were stored, celebrated my birthday on a ship, looked in a number of artist/designers: Enzo Mari, Ruth Asawa, Evan Roth, Max Lamb and others; started playing the new Zelda game, and met as a class to kayak out to an abandoned island to get lost on.

I swear I meant to briefly touch on key points, but the more I looked into it, the more I wanted to share with you about the (literal) connection between Halifax and the internet:

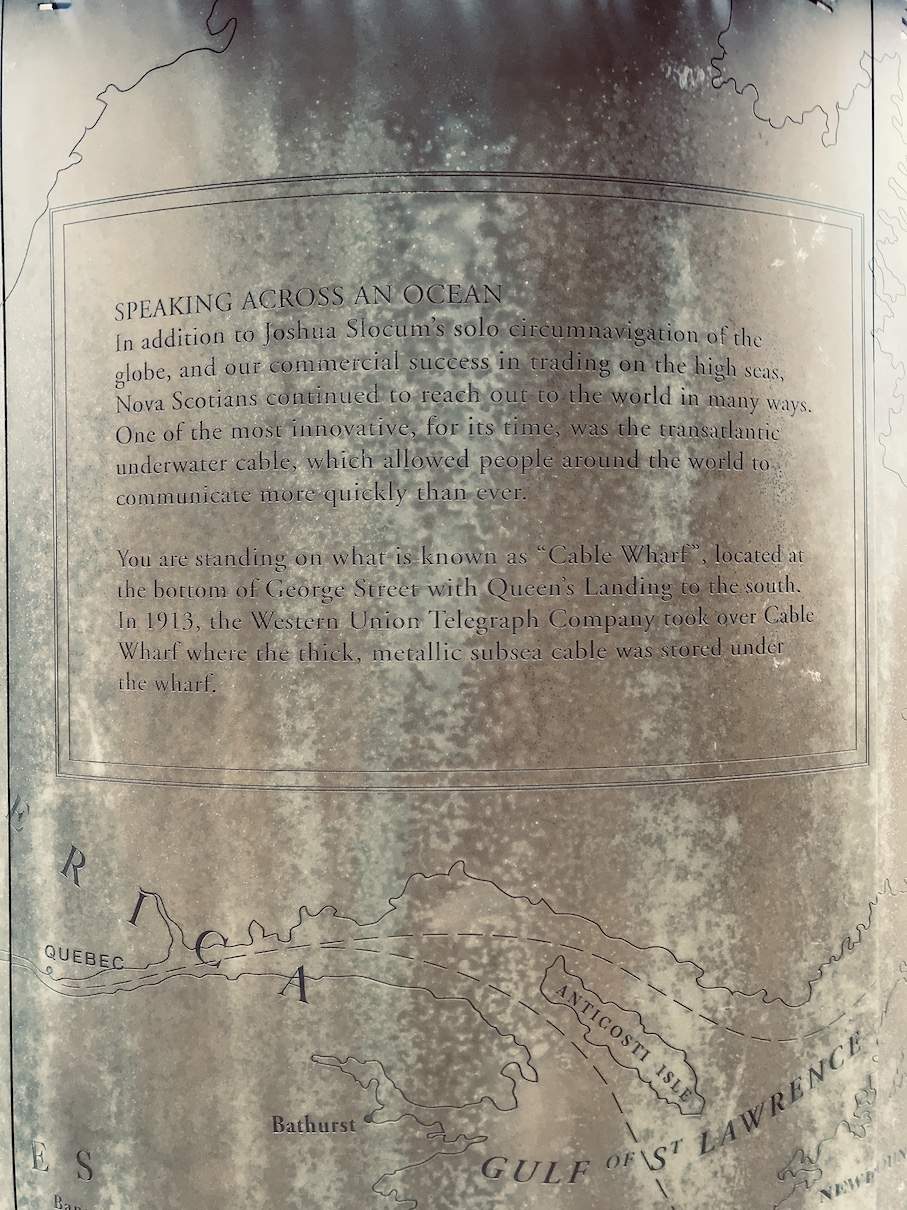

I mentioned towards the end of my last post/letter, I had been thinking about weaving techniques, traps and technology when the undersea cables came to mind; Halifax is the largest city on Canada’s east coast, perhaps there would a connection point– and indeed there is. I briefly googled it, sent the letter, and then headed downtown for a class meeting at the campus by the port. I was walking along the boardwalk when I read a sign for Cable Wharf when lo and behold– a handy information plaque was posted!

on the plaque: Nova Scotians continued to reach out to the world in many ways. One of the most innovative, for its time, was the transatlantic underwater cable, which allowed people around the world to communicate more quickly than ever. You are standing on what is known as ‘Cable Wharf’, located at the bottom of George Street with Queen’s Landing to the south. In 1913, the Western Union Telegraph Company took over Cable Wharf where the thick, metallic subsea cable was stored under the wharf.

on the plaque: Nova Scotians continued to reach out to the world in many ways. One of the most innovative, for its time, was the transatlantic underwater cable, which allowed people around the world to communicate more quickly than ever. You are standing on what is known as ‘Cable Wharf’, located at the bottom of George Street with Queen’s Landing to the south. In 1913, the Western Union Telegraph Company took over Cable Wharf where the thick, metallic subsea cable was stored under the wharf.

Sometime back in 2018 I stumbled upon the work Evan Roth, specifically his work Landscapes, where he went on a ‘pilgrimage’ to “coastal sites where undersea Internet cables emerged from the waters” and documented them in various ways. They’re beautiful images and videos, shot in infrared like “the frequency of the information traveling through fibre optic cables”. They’re not at all the kind of imagery associated with tech infrastructure. Instead the landscapes are often unremarkable, quiet scenes of a shoreline with trees.

%20-9727.jpg) installation view of Landscape with a Ruin

installation view of Landscape with a Ruin

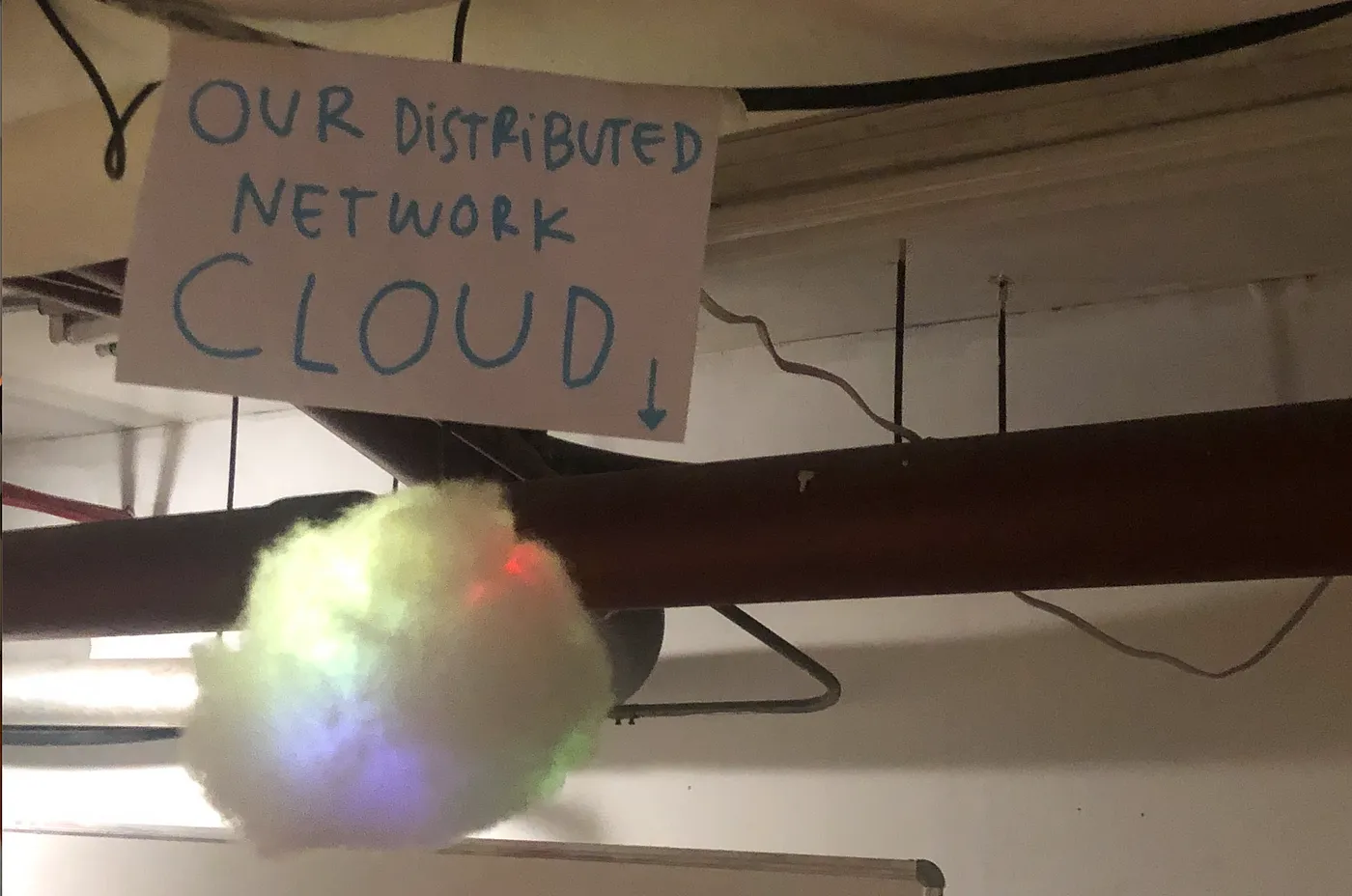

I don’t think I entirely understood it — and I’m still struggling to wrap my brain around it, which is probably why I’m fascinated by this — but in 2019 when I attended SFPC the notion of the physicality of the internet, of computing in general, came up again. Throughout, there was a focus on undoing the myth of the ‘cloud’ and others, these marketing metaphors that simplify and obscure what’s happening inside the ‘black box’ of computers and other technology. We read about the mining of minerals used in computers and the layers of colonialism, racism and classism embedded both historically and currently. We learned about hardware and software and how they go together, but throughout there was a physicality and presence to the technology we were working with: we soldered wires and resistors together to make circuits, and students made a Raspberry Pi ‘Cloud’ server that literally hung above our heads.

A raspberry pi concealed by cotton batting with a sign above that reads ‘our distributed network cloud’

A raspberry pi concealed by cotton batting with a sign above that reads ‘our distributed network cloud’

So it was neat to suddenly find myself standing at a site of the history of the birth of the infrastructure we use constantly.

The Transatlantic cable referred to on the wharf’s plaques was used to carry telegraphs. The wikipedia page for it reads like a Hollywood tale of mankind’s ambition, innovation and perseverance to achieve a technological dream: the ability to send a message across the Atlantic ocean in an ‘instant’, from Europe to North America. Attempts began in 1850s and were fraught with problems: the massive distance between coasts and the sheer amount of cable, the material and construction of the cable (no single wire-rope manufacturer could produce enough needed in time so two companies were hired, yet “Late in manufacturing, it was discovered that the two batches had been made with strands twisted in opposite directions” and so could not be connected without them unspooling), the ships and technique needed to transport and lay out the cable, broken and lost wires at the seabed, as well as the volatile weather.

Major success came when Queen Victoria sent a message to President Buchanan via Ireland — Newfoundland — Nova Scotia to Pennsylvania that took over 16 hours to send. His response:

A triumph more glorious, because far more useful to mankind, than was ever won by conqueror on the field of battle. May the Atlantic telegraph, under the blessing of Heaven, prove to be a bond of perpetual peace and friendship between the kindred nations, and an instrument destined by Divine Providence to diffuse religion, civilization, liberty, and law throughout the world.

The Eastern Telegraph Co. System and its general connections. Chart of submarine telegraph cable routes, showing the global reach of telecommunications at the beginning of the 20th century

The Eastern Telegraph Co. System and its general connections. Chart of submarine telegraph cable routes, showing the global reach of telecommunications at the beginning of the 20th century

Telegraph isn’t used today, but we still use cables to communicate around the world (99% of traffic is the figure that keeps popping up). The above map is similar to what you see when looking at the currently active data communication cables. Halifax is currently connected to Ireland and the UK via the EXA Express and EXA North and South cables, stretching 4600 kilometres and have an estimated 53 Terrabyte per second speed (and this isn’t the fastest worldwide)(source). I would love to find out where the cables come up, like Evan Roth did, and Mario Santamaria does in their Internet Tours! You’ll be the first to know when I do.

However, this is where my brain gets stuck trying to understand the sheer scale of this system people have built. These cables that wrap around the world, connecting every continent save Antartica, all exist down there. It’s not just one cable — those telegraph lines are still down there as far as I know, along with all the failed attempts. Then the phone lines, and then iterations of data cables from the early internet to now. These cables are made to have an approximate 25 year life span, which seems generous when I read that demand for bandwidth is expected to double every two years.

photo of NSA-Tapped Undersea Cables, North Pacific Ocean by Trevor Paglen https://paglen.studio/2020/05/22/undersea-cables/

photo of NSA-Tapped Undersea Cables, North Pacific Ocean by Trevor Paglen https://paglen.studio/2020/05/22/undersea-cables/

The internet is very much physical: underwater landslides have damaged it, sharks have bitten it, and pirates have stolen literal parts of it.

These cables span across borders strategically; of course Canada was involved — Britain dominated the early telegraph cables through its worldwide colonial empire. When it declared war on Germany, one of the first actions was to cut the telegraph cables, forcing Germany to use radio which could be intercepted and listened in on. Submarine cable manufacturers and installation company names may not be familiar, but the current investors and developers are: Amazon, Microsoft, Alphabet (Google) and Meta (currently building the to-be longest cable around Africa to the EU and India).

Finally, one last thing I learned while digging around was the existence of underwater data servers. I knew about the massive buildings full of servers in middle-of-nowhere locations, but there are also underwater capsules containing groups of servers. Microsoft launched a test in 2015 and continued to grow in scale. The underwater server centres benefit from the more stable temperatures underwater, no oxygen or humidity, no humans to bump into components and don’t use up any fresh water for cooling like the land-based centres do. Perhaps this is glimpse at the future of ‘the cloud’: underwater.

Mario Santamaria’s Cloudplexity, representations of the internet from the US Patent office

Mario Santamaria’s Cloudplexity, representations of the internet from the US Patent office

I think there’s some connections and open threads of ideas here that I like:

This post was shared to friend’s inboxes through my newsletter. You can subscribe, here, if you’d also like a letter to your own: